This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to the Curbsiders. I'm Dr Matthew Watto, here with my great friend, Dr Paul Nelson Williams. We are going to talk about hemochromatosis. Paul, this condition scares me; I didn't understand it that well before our talk, Hemochromatosis with Eliot Tapper. How about you?

Paul N. Williams, MD: It still scares me, but now in a different way. Have I been looking for this as aggressively as I should have? I feel like I have a better handle on it now.

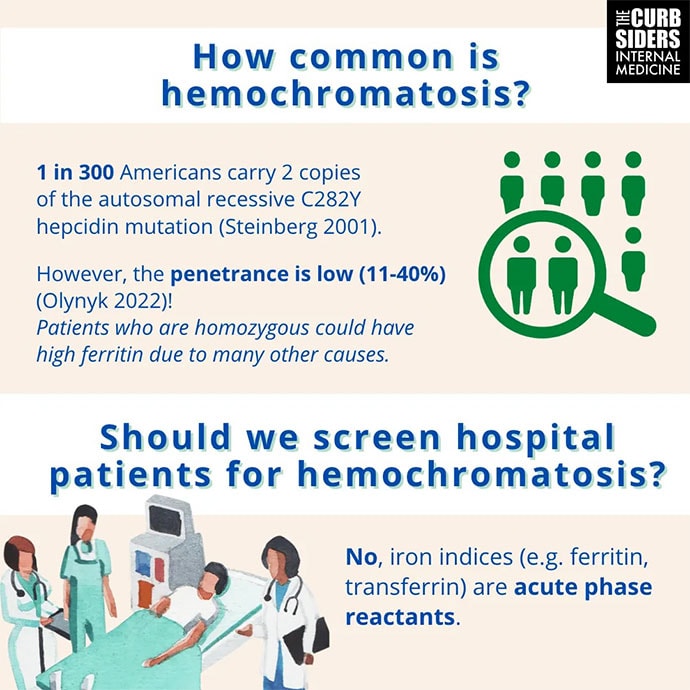

Watto: One of the big take-home points from this episode is that the mutations that can cause hereditary hemochromatosis are pretty common, but the penetrance is very low and variable. So not everybody, even if they're homozygous for the mutation — and C282Y is the most common — even if they have two copies of that, they might not have hereditary hemochromatosis. What's probably more common is the patient with dysmetabolic iron overload. Have you ever heard of that?

Williams: I had not heard it referred to in that way, but it makes a lot of sense.

Watto: This is where the patient has metabolic syndrome and some inflammation of the liver. The serum ferritin level can be elevated in the same way that you might see with hereditary hemochromatosis. Dr Tapper said that before he sends genetic testing on a patient with a high ferritin level, if they have metabolic syndrome, he'll try to work on weight loss, improving their lifestyle, and if they are drinking alcohol, that can also drive the ferritin level through the roof. He'll try to get them off of alcohol and improve their metabolic health, and then repeat the levels and defer genetic testing. This is his expert opinion. The guidelines will usually tell you to just do the hereditary testing right away. But because of that low penetrance, you can go down a bad path if you do the genetic testing and then you have a patient convinced they have hemochromatosis even if they don't.

Williams: On the inpatient side, a ferritin level is checked for God knows what reason half the time; maybe the hemoglobin is slightly low. During COVID-19, it was part of the order set in some institutions. Don't forget that it's an acute-phase reactant. If someone has a lot of inflammation, the ferritin is going to be high in the same way that chronic low-grade inflammation in the outpatient setting will push the ferritin up. If the patient has an acute process (like infection or malignancy) going on, or hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), that's not hemochromatosis. You should probably let them cool off. You should not rely on inpatient labs to start your diagnostic considerations for hemochromatosis unless there's some other compelling reason to do so. The right practice is probably to get them off of whatever acute thing is happening. Do your follow-up labs in the office and then if they are still elevated, start thinking about what could be causing this and then go down that particular rabbit hole.

Watto: I wasn't sure if I should call you a show-off or give a standing ovation for pronouncing HLH correctly. That was fantastic.

Williams: I was practicing in my head before we started recording.

Watto: What numbers should people look for in women and men? They're slightly different, but basically, if the ferritin is > 200 to 300, or if the iron saturation is > 45%-50% (depending on whether it's a woman or a man), then you would consider that the patient could have hereditary hemochromatosis. In Dr Tapper's practice, he would try to get them off alcohol and improve their metabolic health before getting too worked up about those numbers. But those would be the numbers you'd find over time. If the ferritin level remains > 200 and the transferrin saturation > 45%, you can consider sending the genetic testing, with the appropriate counseling. If you find hereditary hemochromatosis, you should really stage the liver. Liver biopsies for everybody, Paul?

Williams: Happily, we now have good serologic measures, so we don't have to be setting small pieces of liver on fire to look at the iron content. We have other ways of looking at inflammation.

Watto: He threw out there that you can calculate a Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) score. Of course, we should check their bilirubin, albumin, platelets, and coagulation tests (coags) — the normal things we would look at if we had concern for cirrhosis. There is also elastography, which can be done with an ultrasound type machine, or the MRI version, and that has largely replaced liver biopsy for determining whether someone has advanced fibrosis.

Williams: It's very reasonable to ask why we have a liver expert talk about this hereditary iron overload state. The classic things that we learned in medical school — like the bronze diabetes presentation of hemochromatosis — is just not the way that we're seeing it. The liver is most common way that you're going to find hemochromatosis. So unfortunately, one more medical school teaching, while not untrue, is not nearly as useful as we were led to believe. It's going to be the liver first, which is why it's so important to make sure that you're doing that staging.

Watto: If you haven't heard one of our episodes with Dr Elliot Tapper, he is an amazing guest. You should listen to anything that we do with him and follow him on Twitter because he is fantastic.

This has been another episode of the Curbsiders bringing you a little knowledge food for your brain hole. Until next time, I'm Dr Matthew Frank Watto.

Williams: And as always, I'm Dr Paul Nelson William. Thank you.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Credits:

Images: The Curbsiders

© 2023 WebMD, LLC

Cite this: Matthew F. Watto, Paul N. Williams. Hemochromatosis: What We Should Have Learned About It - Medscape - May 22, 2023.

Comments